IMDB / Ebert / Hornaday

Starring Stephen Dorff and Elle Fanning

Written and Directed by Sofia Coppola

Rating: H (Highly Recommended)

Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere is like Jackass without the stunts, or maybe Jackass when the camera isn’t rolling. I’m not just saying that because of the presence of Chris Pontius, that laconic joker famous for his ‘Party Boy’ antics. Somewhere is almost Dadaist as Coppola lingers on bizarre showbiz images such as its star covered in putty for a face mould, or a ludicrously bombastic Italian awards ceremony, and gently pulls down the façade of Hollywood nicety with a subtle, non-judgmental eye. Johnny Marco, the nearly mute anti-hero, bounces from one corner of his irrational movie star life to another – rich, unsatisfied, stagnant.

Enter his daughter Cleo, the Figure of Redemption, but don’t worry. It isn’t that kind of movie. We can only assume that prior to the events in the film, Johnny saw Cleo on a semi-regular basis but was too wrapped up in endless parties and women to truly notice her. Now, as a result of certain circumstances, she’s going to be more present in his life – for a while, at least, maybe just long enough to make a difference.

Really, it’s okay, it genuinely isn’t that kind of movie. I mean, it is: a classical story, lost and/or deluded and/or miserable soul has his life thrown into perspective by the arrival of someone with simple, innocent meaning and purpose, both in her own intentions and in her relevance to our anti-hero’s life. What’s different is that Coppola takes this story, so often overdone and blandly unsubtle in films, and strips it back to the point of elusiveness. We witness a series of disconnected moments, often played out with a near-total absence of dialogue, and rather than there being an obvious narrative thread, it’s more our own expectation that creates one.

As a result, Somewhere will be infuriating and – even worse – incredibly boring to some viewers. For those who are willing to go along with Coppola’s sound- and image-focused style and put the idea of a Good Story to one side, however, Somewhere is a meditative treat, a joy. It even approaches the divine as she pulls the whole thing together in a glorious, grand (yet still understated) finale, stretching out the back end of Phoenix’s ‘Love Like A Sunset’ – with its eerie Wendy Carlos synthesizer and subsequent glorious release – in a moment of true movie magic that I could not resist.

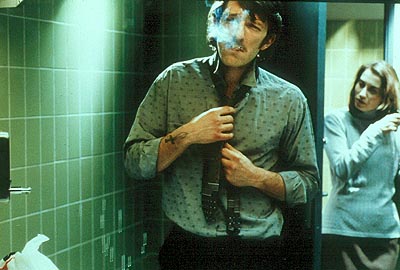

Stephen Dorff is very watchable in the central role; I particularly liked the fact that despite being a big movie star with an endless parade of half-naked women fawning around him, he never comes across as a total dick. He’s polite to people whether he knows them or not; perhaps the stream of ‘you are such a fucking asshole’ SMSes he receives are the result of a prior attitude we don’t get to see. Then there’s Elle Fanning, who is an utter delight as his daughter. She’s just the kind of daddy’s little girl that fathers would want to do absolutely anything for: cute, sweet, talented. The key phrase there is that Johnny does indeed want to do anything for Cleo, but it’s evident that in the past, he simply hasn’t.

Neither of these two is the star of the film. That would be Richard Beggs, sound designer extraordinaire, who would also have been the star of Lost In Translation as well if it hadn’t been for the incomparable Bill Murray. Somewhere needs to be watched with the best sound possible so that you can appreciate the space of each scene – the grumble of Johnny’s Ferrari, the crackle of his cigarette as he smokes it down to the filter. Combined with another well-employed score of popular and atmospheric music, Beggs has crafted an aural wonderland yet again.

And then there’s Sofia Coppola, who by now has leapt well and truly out of her father’s shadow artistically. She stays within her limitations as a filmmaker, but what fascinating limitations. Her productions feel a little like really expensive student films in their scope, spare and mood-focused, and she is fortunate to have all the backing and support she could ever need (just check out those names in the ‘Thanks’ section of the credits). We’re fortunate that she uses that support to give us images of unexpected beauty in emptiness, like Johnny drifting lazily out of frame on a yellow Lilo inflatable sunlounger in the hotel pool, or his near-catatonic plucking of a pear from the fruit bowl on his coffee table, only to return it seconds later.

You may not learn anything from Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere, save for a few insights into the private lives of Hollywood stars. If you’re willing to submit to her freeform approach to filmmaking, though, you’ll be rewarded with another immensely satisfying tone poem of real lives and subtle movie magic. It’s not as good as Lost In Translation, of course, which she is unlikely to better even if she makes movies for another 50 years, but Somewhere is fit to be mentioned in the same breath, and it stands firmly on its own as a showcase for the gifts of sound and vision.